ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Bulgari's new Octo Finissimo collaboration with Lee Ufan is not just one of the best Octo Finissimo to come from the Maison in the history of the model, but also the most captivating and wounding collaboration I've seen between a watch brand and an artist. Neither achievement is a small feat, but after handling hundreds of watches per year, it's unusual that I find myself genuinely moved by a watch – not just impressed by its technicality, finishing, value, or history, but actually moved.

The framework should be familiar, a 40mm by 5.5mm titanium Octo Finissimo case with no indices, just a gradient mirrored dial and blackened indices. Inside the case is the BVL 138 micro-rotor movement with 60 hours of power reserve (a sizeable amount for such a small movement) powering the hours, minutes, and seconds.

Then there's the case, which is hand-filed and renders each unique. If you can wear a 40mm Octo Finissimo, it will work for you; if you can't, it won't. There's hope for more options in the future. That's self-explanatory enough to cap off a hands-on for a watch with a well-known framework. That's not what I want to talk about.

This talk of emotion may be too saccharine for many. The increased collector focus on retained value and investment makes sense as the hobby has grown and prices have risen; understandably, people don't want to feel like they are throwing money away. I see comments all the time debating design, quality, finishing, and product specifications, but so little discussion about how a product makes you feel. If you're not feeling nearly as open to emotion as I apparently am while writing that, it's okay. However, it's important to remember that emotion is a core part of enthusiasm for watches (or really, anything).

Fabrizio Buonamassa Stigliani, who famously starts his designs on paper, but eventually paper isn't the best format for a watch.

And yet too much emotion can be too much of a good thing. While I haven't read other coverage of the model, I imagine that much of it focused on stories Fabrizio Buonamassa Stigliani, Bulgari's Product Creation Executive Director, shared with me and various people in interviews throughout the week about the challenges of collaborating with artists. But I want to go a bit deeper.

I love art, and I find conversations with artists fascinating, but if you've ever read an artist statement, you can understand how often they're "idea people." While powerful ideas make for powerful art, an artist differs from the perspective of an industrial designer, who has the remit of creating a practical, usable object. That object can be beautiful, captivating, and interesting, but as Buonamassa Stigliani used as an example, an artist who suggests making an Octo Finissimo out of paper doesn't think about the practicality or longevity, only the impact of the idea. As my old art photo professor once told me, if the idea of something is enough for you, file it away in a box under your bed and be content with it. Or else make something and put it into the world.

Bulgari Octo Finissimo 'Sejima' Limited Edition.

But then there's the impact when you get it right as more than just an idea, but a wearable object. The original Octo Finissimo "Sketch" limited edition is sort of a self-collaboration between Buonamassa Stigliani and himself, but it was the right touch of creativity without being overblown. Before this watch, it was my favorite limited edition. The Tadao Ando releases found success with collectors and are probably the brand's most beloved. The Sejima watch, on the other hand, was maybe more divisive but more impactful for that divisiveness. Yet collectors loved it for its surprising and creative nature; Auro Montanari, for instance, owns one of the latter. What I find interesting between the two is how the brand continually draws on the well of Japanese art.

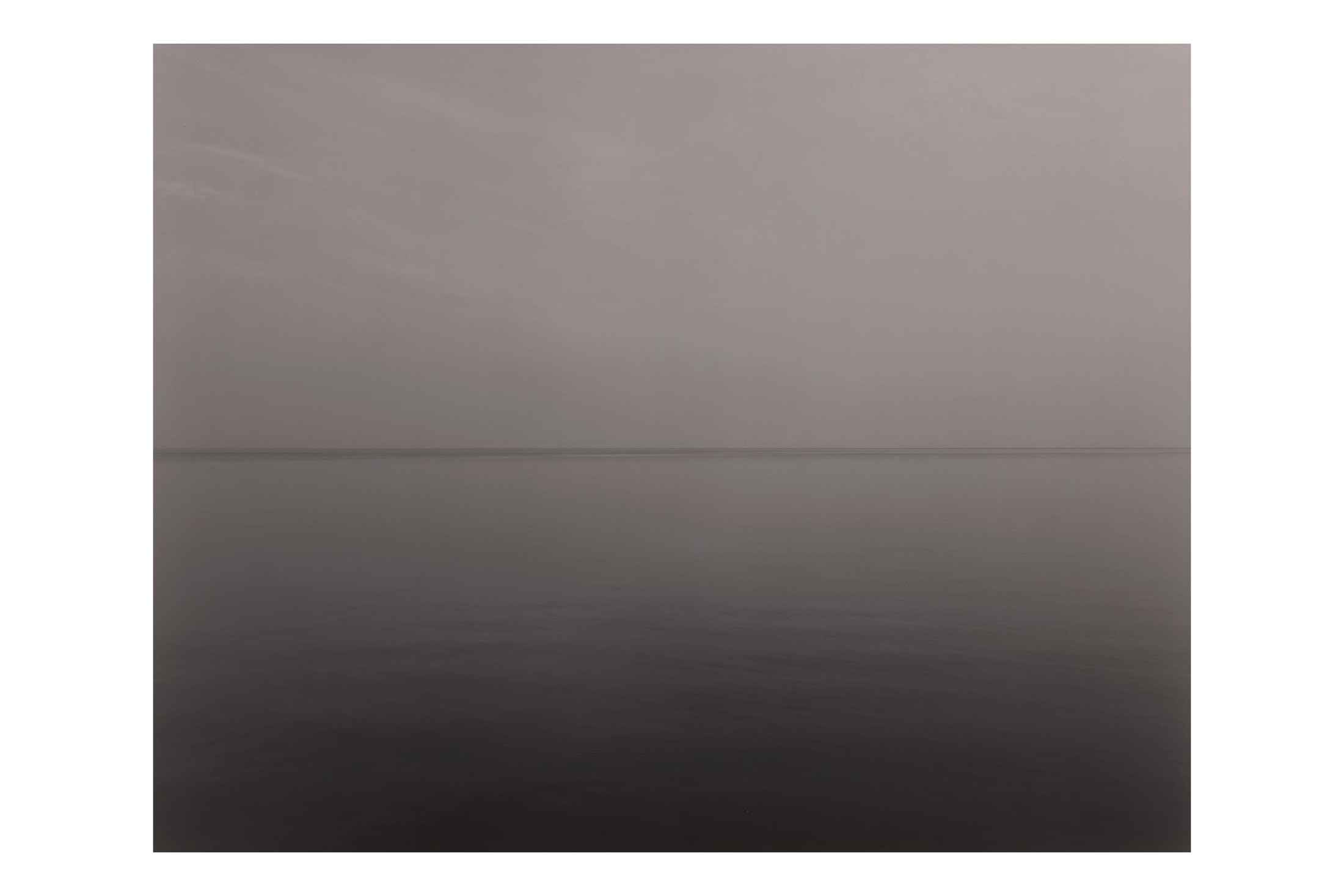

There's something captivatingly beautiful about some of Japan's most reserved, refined, and melancholic contemporary artists. It's a far cry from the bright, colorful polka dots that Yayoi Kusama uses (and has used with Louis Vuitton, for instance), but I don't think the Octo Finissimo lends itself to such vibrance. In fact, I think it's at its best when using the same adjectives I just used, and could describe my favorite Japanese artists, such as Hiroshi Sugimoto or Jiro Takamatsu. Even American-born George Nakashima lent some traditional Japanese perspective in his work, with his furniture having the goal of being unobtrusive yet beautiful and thoughtful of how it brings natural form into the home. I once was told that my Midwestern sensibility, that "my existence is an inconvenience to those around me and my job in life is to minimize that fact," is almost identical to Japanese cultural identity. Perhaps that's why I find a certain kinship in the introspective, melancholic artists of Japan.

Hiroshi Sugimoto's "Lake Michigan, Gills Rock" taken not far from where the author's family lives. Sold at a Phillips Auction in 2024. Photo courtesy Phillips.

If there are two ideas I use frequently when discussing with designers, it's that first and foremost, an object works or it doesn't. Something good achieves the goals that you set out for it to be, as a holistic form that is functional, beautiful, practical, or whatever you designed it to fulfill, and the success or failure is self-explanatory in short order. That's why I often can tell, or rather feel, watches designed by committee, where one little issue of balance throws off the whole piece.

There's usually too much noise and no one solid voice. To be fair, I'm not a designer. I'm happy to provide feedback, but as a photographer, I've never had to create from scratch. So, in that way, I can always say why something may or may not work; it's the benefit of being a commentator, I suppose. But when it does work, the discussion on the object is somewhat superfluous, because it's only part of the picture.

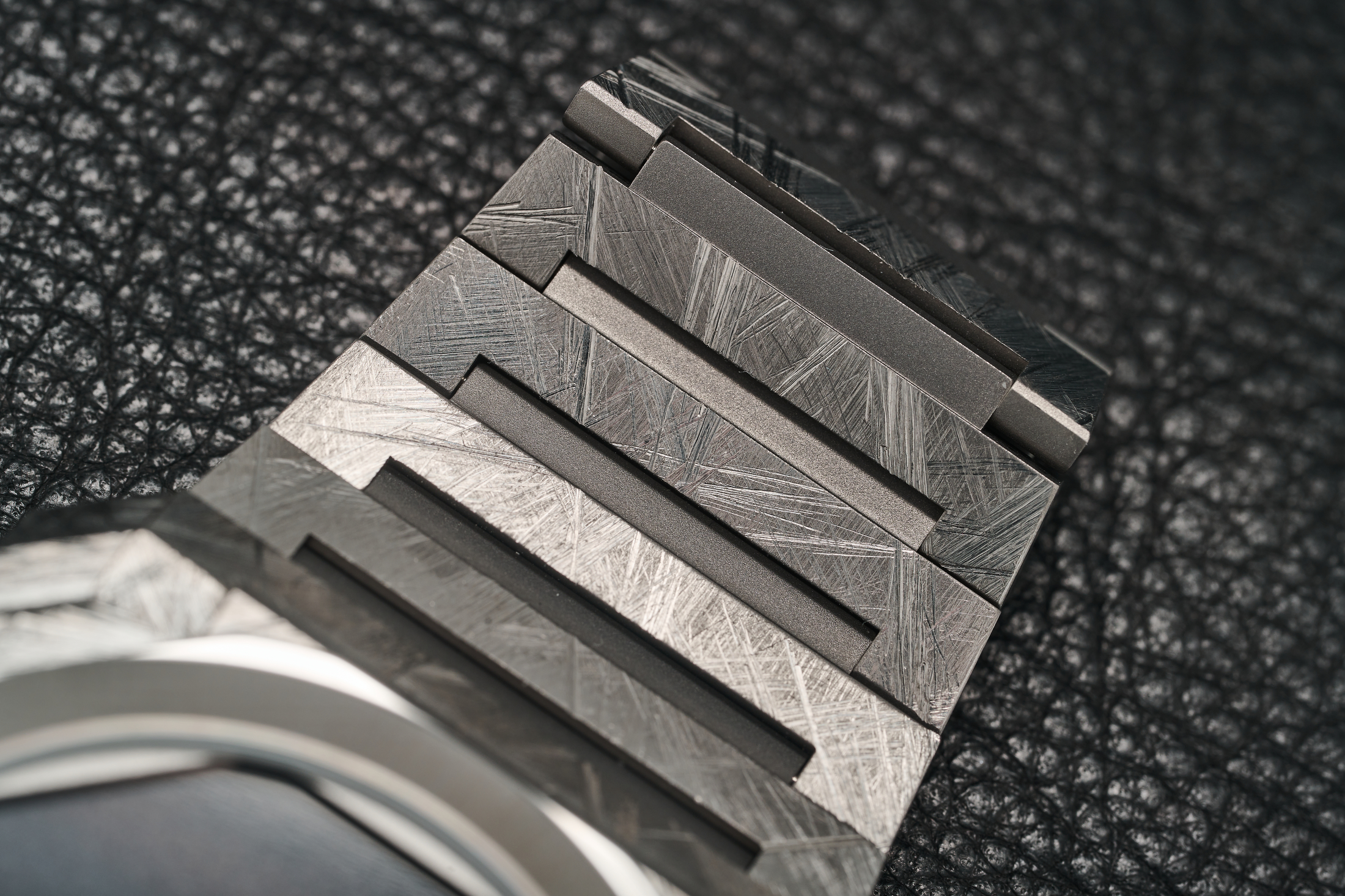

The Bulgari Octo Finissimo Lee Ufan limited edition works as an object. The interplay between the rough-hewn surfaces of the titanium bracelet and the soft, reflective gradient of the dial is harmonious, even if viewed in a vacuum. It looks like a meteorite with its top lopped off, polished to a shine. But without understanding the artists behind it, you miss the forest for the trees.

Lee Ufan is South Korean by birth, but his influence on the Japanese artistic and cultural landscape can't be overstated. In the modern landscape, he's collaborated on two museums under his own name (one in France and one in Japan) with the aforementioned Tadao Ando. However, before that, his work laid the foundation for the post-war Japanese art style Mono-ha, which explores the interplay, interdependency, and clash between industrial landscapes and nature. Clash might be too strong a word, as his art is thoughtful, reserved, and beautiful, but pointed nevertheless.

If you look at work like his 1968 piece "Phenomenon," or at the landscapes of the grounds in his museum in Naoshima, you can see the interplay between the rough surfaces of nature and industry. I'd also recommend visiting the Lisson Gallery website to look at "Relatum – Rest, 2013." Rocks sitting on polished steel and glass reflect themselves like a pond, but question what we lose when we lose the pond and replace it with something so refined and synthetic. And yet, like so much art, it is entirely impractical for my life or living in a New York City apartment with nowhere to put a boulder.

The Lee Ufan limited edition can turn dark and moody, but not quite the same as the Sejima Limited Edition from a few years ago.

The Sejima Limited Edition, shifting in the light.

From mirror to black.

This is another example I use frequently, borrowed from Roland Barthes' "Camera Lucida:": the studium and the punctum. As a treatise on photography, the studium is basically everything within a frame of a photo that is technically correct (the exposure, the angle, the lens that was chosen). The punctum is the emotion, moment, or imperfection that draws you in. The punctum is the thing that "wounds you." The "wounding," in Mono-Ha, is the same dichotomy that I feel in life: drawn to places of nature and beauty like my home in Wisconsin, as core to my identity and upbringing, pulled toward the industrial and bustling landscapes of New York for work. It's the push and pull of industry and nature that I find so interesting, and instead of being nostalgic like most of the work I love, Ufan is much more pointed with his voice.

The Octo Finissimo is the perfect canvas for collaboration. But I don't feel like I've been "wounded" by any previous collaboration in the same way. Yes, the Sejima watch plays with light. The Tadao Ando collaborations play with texture. This combines the two in a way that speaks to Ufan's body of work. The core of Mono-ha was the idea of "not making," because technology had supplanted the need to create anything new, but instead of reinterpreting what had already been made. It's all the more appropriate then, when I think about Buoamassa Stigliani, setting to work on an otherwise normal Octo Finissimo and transforming it, using a triangular file to file away at the case until this meteorite-like design emerged. I can't imagine what his team thought, looking at all the titanium shavings sitting on his desk as he worked away, but the result is spectacular. The framework is the studium, but what was created wounds.

The Lee Ufan and an example of the same case before it was filed (at left).

Buonamassa Stigliani is not just a great interpreter of art, but a great photographer in his own right; a look at his Instagram makes that apparent. However, as someone who has been a photographer (primarily of people and places) for his entire career and views photography with a critical eye, what I've come to appreciate is his ability to take a complex environment and distill it down to its core, finding quiet in chaos. He achieved this through his collaboration with Lee Ufan, creating a $20,000 piece of wearable art.

Fabrizio Buonamassa Stigliani and Lee Ufan. Photo courtesy Bulgari.

The case remains architectural; the same elements that made it work as a canvas for Ando still stand, but with a heavy hand of work creating a more natural texture. The dial, which shifts in the light and goes from the built-in gradient to a solid black in the shadow, elicits the same feeling of dark waters that you see in Ufan's sculptural work, but is also reminiscent of the gradients in Sugimoto's "Seascapes."

It reminds me of the views over the water in my family's home in Wisconsin, as warm air rolls across the cold water of Lake Michigan, blanketing the landscape with a gradient of fog. It's not depressing, really; it's just comforting, cutting out noise and focusing the senses. The entire watch takes the expectations you have for most watches—the dial being the canvas and the bracelet supporting it—and turns it into something else.

Kangaroo Lake, Wisconsin. 2021. Photo by Mark Kauzlarich.

I don't buy many watches. I like to think about it, wish I could, and/or vacillate about them. When I truly yearn for something, it's because of that emotion, the people behind it, and the "why" that makes it interesting. It's that reason that this is one of the watches I would love to add to my collection. The object here works, but it's everything else that makes it fantastic.

For more information, visit Bulgari.

Top Discussions

IntroducingDoxa Sub 300 Carbon Seafoam Limited Edition

IntroducingBaltic's Dive Watch Gets A Facelift With The Aquascaphe MK2

Hands-OnThe Timex Marlin Quartz GMT